Courtesy of Larry Pletcher

Charleville Musket

Firing

and

Cleaning

Revolutionary War Musket

The "Revolutionary" Charleville

Charleville Musket

Charleville Muzzle-Loading Musket

Charleville Flintlock

Musket

Charleville Lore

"The Model 1766 Charleville is based on the first regulation French military musket -- the so-called Model of 1717. The Pedersoli (Italy) reproduction features a European walnut fullstock 57 1/2" long with satin finish, 2 1/2" drop and 13 1/4" trigger pull. [Steel] barrel is armory bright .69 caliber smoothbore, round tapered 1.300" at breech to .840" at muzzle. [In comparison, Brown Bess is .75 caliber with .69 caliber ball.] Flintlock uses 1" [1" wide x 11/8 " long] flints . All steel furniture is armory bright, [steel] lockplate is marked "Charleville." Steel ramrod with trumpet shaped head and 10x32 thread. Gun is 60" in overall length and weighs 10 1/2 lbs. Load with 80 grains* FFg black powder and patched .680 round ball." Dixie Gun Works [Note: Model 1766 {Light model 1763} Charleville normally came equipped with a button-head ramrod. Trumpet shape usually came with Model 1763 or 1773-77 Charlevilles. Common that current suppliers also provide Model 1777 bayonets (with center locking band; although not generally supplied by the French to the colonists, the French fighting alongside the colonists did have them on their Model 1777 Charlevilles). Also, at Yorktown the Americans were using a .643 ball called a #19 ball, as there were 19 balls per pound of lead. At 16 ounces per pound, this puts one of these balls at 0.84 ounce or almost 1 ounce.

Note: Webmaster's Pedersoli 1766 Charleville [with 1763 or 1773-1777 trumpet shaped ramrod] is 60 inches long and weighs 10.4 pounds. With 1777 bayonet, it is 77 inches long and weighs 11.2 pounds. George Neuman, in his book Battle Weapons of the American Revolution, states "The Model 1763 was quickly found to be too heavy. This revised 1766 Pattern kept the basic configuration but reduced its original weight." He lists the 1763 Charleville as being 9.2 lbs and the 1766 Charleville as being 8.5 lbs.

Notes: According to the following site ( http://www.littlegun.info/arme%20francaise/collection%20fusils/a%20a%20collection%20fusils%20tir%20fr.htm), the Charleville used a .65 caliber ball with over 154-185 grains of "musket" powder for the cartridge (included priming powder). It's been reported that Hoyem's History and Development of Small Arms Ammunition says that around 1776, the French muskets were of .69 caliber, with ball diameter of .63, and powder charge of 189 grains, 10 grains of which were used for priming. Maximum effective range: 100 to 200 yards max; average effective range 50 to 75 yards (see more on weapon ranges below). Fortification designers planned on "musket shot" range of 300 yards regardless of inaccuracy. Beware: widely varying claims exist for the correlation between current black powder and Rev War era "musket" powder. After its powder was emptied into the barrel, a paper cartridge with ball enclosed was rammed down the barrel, ball first, acting both as wadding and ball stabilizer (for better accuracy), similar to the patch mentioned above by Dixie Gun Works. While Washington's troops at Yorktown used a bore #19 ball (19 balls per pound) with .643 caliber, this size ball (then made at the Fifth Street Laboratory in Philadelphia) is hard to find. G. Eddie May has sold .648 caliber (16 gauge shotgun) round balls for the great price of 20 cents each (postage extra). You can contact Eddie for current pricing for this and other sizes at 706-581-8225. Eddie's mailing address is 159 Ridley Rd, Chatsworth, GA 30705-5757.

Firing musket videos:

Shooting the 1766

Charleville Musket

Charleville 1766 Tips

West Point Flintlock Video

Revolutionary War

Soldier Explaining [Charleville] Flintlock Musket

Firing a Musket:

18th-Century Small Arms

Revolutionary War

Musket Bunker Hill July

2009

Why a

musket???

Why a

musket??? part

2

Musket Firing at Concord

Brown Bess Musket -- Three Shots in

46 Seconds*

Brown Bess vs the

Charleville Musket

Charleville Accuracy Test

How to Fire Brown Bess

Musket -- English Heritage

Firing a

Flintlock Musket

Loading and Firing a

Musket

Lexington

Concord Battle Road Minute Man National Park

Rifle and

Musket Demonstration

at Valley Forge

Revolutionary War Re-enactment [2005

at Cantigny- Wheaton, IL]

The American Revolution in 4

breathtaking minutes!

Bullet-making 1

Bullet-making 2

Cartridge-making

Reenactment

Cartridge-making

Slow motion video of musket firing upon breastplate

Note difference in Rev War vs. later method of

putting ball into barrel and in determining rate of fire. Those claiming

five shots per minute usually started with a loaded musket and jammed the ramrod

into the ground as opposed to returning it to its slot in the musket between

firings. Best otherwise is four shots per minute. Brown Bess* expert above

almost makes the rate of four shots per minute (starting unloaded, 3 shots in 46 seconds is

3.913 shots per minute). Perhaps the four shots per minute rate, per some

familiar with smoothbore history, is that the soldier likely used an undersized

ball and did not use wadding, so nothing was needed other than to drop a ball

down the barrel after pouring in the powder (no wadding or ramrodding

required) and stomping the butt on the ground. This is also said to

possibly explain the Loyalist loss at Kings

Mountain: they were shooting downhill, and the balls would fall out,

necessitating the slower reload time with wadding (counter-argument is that

fouling would have prevented the balls from rolling out). Usual firing rate with

wadding is three shots or even just two shots

per minute (view Brown Bess Musket -- Three shots in 46 seconds (again, starting

unloaded)). One expert remembers reading that

during

the War of 1812, the British standard procedure was to not bother priming the

pan. The ball traveling down the barrel when loading will force powder out of

the vent into the pan, so with both procedures (no wadding/rodding & no

priming), perhaps four shots per minute was possible for many soldiers. Washington Post says 3 shots/minute and accurate to 55 yards. One expert [Allen Guelzo] claims the "inverse," that, in the

fog of war (smoke-filled, anxiety-ridden battlefields), it was more likely that

a soldier would fire one shot every three to five minutes. Remember

that soldiers would not only be on the move but watching their comrades die

beside them. Colonel

Light Horse Harry Lee in his memoirs admiringly describes an American regiment

at Brandywine which fired 30 rounds per man in 45 minutes (0.66 rounds per

minute or 1.5 minutes per round). Comparatively in the best of

circumstances, rifles might fire one shot per minute with frequent barrel

fouling due to powder residue build-up. Common for musketeers to fire

three shots and then charge with the bayonet to hopefully make the enemy break,

run, or otherwise flee the field.

Mathew Spring's research says the British preferred to

close to within 75 yards of the enemy, fire a volley, and then charge with the

bayonet (what amounted to a modified pike or spear). In the time it took an opponent to reload, well-trained soldiers

could outrun the range of a musket. These tactics brought them victory more often than not. Realize that the tactics at the time were a result of the technology available,

with tactics normally following but sometimes inspiring technology.

The musket was a "point and shoot" weapon, known more for its volume than

accuracy of fire (similar to today's 2-pound lighter M-16). Washington

even ordered the front sites of the Charlevilles removed to reduce his soldiers'

temptation to aim, which took time away from producing deadly walls of balls,

where it was the weight of lead, not the accuracy, that carried the day.

(See Comparative Accuracy Notes near the bottom of the page)

As well as the walls of lead, massed firing also intimidated through

concentrated noise. Keeping musketeers close together allowed for effective voice commands given on

a noisy field of battle, when half the battle would be fought in well-timed

(often after the other side had discharged its weapons and before it could

reload) and cohesive bayonet charges much like Greek phalanx attacks.

Thus battlefields were chosen for their cleared, deforested, unobstructed, and

even land. Through both bullets and bayonets, victory went to the side which could drive its opponent from the field.

As a side note, in the 1977 edition of "The Shooter's Bible," G.M. Horn wrote that, at Lexington

and Concord, only one bullet in 300 found its mark and that only one man out of

15 (6.6%) hit anyone. National Park Service statistics show that a Rev War

soldier had a 98% chance of coming out of the average battle alive (but, if

wounded, only a 75% chance of coming out of an army hospital alive)! Other

info: misfire rate is commonly reported to be between 1 out of every five

or six shots on average (18%), though some muskets hardly ever misfire:

the flint is properly set, with neither its underside or the frizzen being

sooty, and the touch hole being free of obstruction.

Adjusting for all the "windages," it might be fair to say that, as a

general rule, a rifle was twice

as accurate as a musket, but could only be fired at half the rate and, unless it

had a rare, specialized socket-bayonet, was useless as as a spear or pike,

and with its slender stock, only lasted so long as a club before it was ruined

as a weapon.

NB:

From Dr. Jerry D. Morelock's

"Washington

as Strategist: Compound Warfare in the American Revolution, 1775-1783" in

"Compound Warfare: That Fatal Knot"

"Conventional

battles between regular forces in the eighteenth century were generally

characterized by parallel lines of troops (hence the term linear tactics;

"firing en masse at a mass"). These

troops faced each other with muskets and bayonets across a distance that was

often only a few hundred (or even a few dozen) yards. Constrained by the

technology of the era

– epitomized

by the use of inaccurate, smoothbore muskets

–

an army seeking victory depended upon troops drilled to stand in massed ranks

and deliver volley after volley of massed fire into its opponent’s lines until

one side or the other could advance as an unbroken battle line with fixed

bayonets to finish off the enemy. Generally, it took about two years of

intensive training and constant drilling to produce a soldier capable of

executing the intricate maneuvers required for this automaton-like fighting (to

underscore this fact, Frederick II the Great, King of Prussia, and the master of

linear tactics, referred to his soldiers as “walking muskets”). The difficulty,

even impossibility, of irregularly trained and indifferently drilled militia

troops executing these tactics is obvious."

NB: From Paul Lockhart's

"Firepower: How Weapons Shaped Warfare"

"One seemingly minor innovation had a measurable [no pun intended] impact

on the musket's rate of fire: the self-contained cartridge. This, too,

came from the fertile military culture of Gustavus Adolphus's Sweden." ...

"The flintlock, muzzle-loading, smoothbore musket, with triangular bayonet,

would remain the main weapon of the European (and American) infantryman from the

early 1700s to around 1840." ... "For an experienced musketeer, the whole

process of loading and firing took twenty seconds or less, making possible a

rate of fire of about three (or more rounds per minute." ... "It was

possible to fire even faster per minute, at least so long as the musket remained

clean. French soldiers were trained to fire four to five rounds per minute

with the flintlocks. In Prussia at the time of the soldier-kings Frederick

William I (r. 1713-1740) and his more famous son Frederick the Great (r.

1740-1786), speed loading became an obsession. The Prussians introduced a

double-ended, heavy iron ramrod for their muskets, sparing each soldier the

awkward motion of twirling the ramrod over his head before inserting it into the

muzzle, and thereby saving maybe a second or two in the process. In the

1780s, they introduced a musket with a conical venthole, so that powder from the

breech could actually flow backward through the vent and into the priming pan—a

self-priming musket, in other words. So it's possible that eighteenth-century

musketeers could fire as fast as five rounds per minute—the musket loaded,

raised, aimed, and fired in the space of twelve seconds—but that could hardly be

sustained in combat." ... "Three rounds per minute is probably a good overall

estimate."

NB: From Arthur S.

Lefkowitz's "George Washington's Revenge"

"A reasonable estimate is that an expert rifleman armed with an American long

rifle could hit a target at 250 yards. In camparison, the smoothbore musket,

which had no grooves (rifling) had an effective range of 100 yards. Claims

that American long rifles had a range of up to 400 yards may be based on firing

modern reproduction weapons using high-quality black powder."

Firing:

For reenactment cartridges for most modern-made

replica muskets, consider using no ball with 60-100 grains of black powder,

likely 3FFFG for extra smoke. 85 grain cartridges will work fine for

reenacting.

Note: Charleville pistols, like most pistols, max at 75 grains per

cartridge for safe reenacting.

Maximum allowable per safety officer usually ranges somewhere between 110 and

120 grains.

Check first with your safety officer!!!

Do not use modern smokeless powder!!

Note: If a pound of powder is 7,000 grains, then, with 100

grains/shot-cartridge, a pound can of powder should yield 70 shots. At 85

grains/shot, a pound powder can should yield 82 shots.

Some reenactors use about 117 grains per cartridge, yielding about 60 shots per

pound of 3FFFG powder. If 20 each 85 grain

shots were used per battle, with four battles per event, a two-day, four-battle

event would require a pound of powder.

Instructions and video of cartridge assembly:

Video of cartridge with

ball.

Video of reenactment cartridge-making .

Discussion of firing buck and ball.

For firing with ball, use only what musket manual states, likely FF Grade (not FFFG) powder in proper amount!

Before firing, assemble flint jaw and install flint

(with leather or (preferably) lead holder) with sharp forward edge aligned so

that it will squarely meet the top 1/3 of closed frizzen to generate sufficient

spark. This may mean that you have to invert the flint. Consider

carrying a nail in your cartridge box should you need need to field-adjust the

flint jaw. [On average a flint may last 30 shots without knapping.

At 15 shots per battle, this may last you a two-day event.]

Ensure that left side of flint will not hit barrel when trigger pulled.

Tighten jaw so that flint will not slip.

Video of fitting gun

flint.

Study in article by Black Powder Magazine found no difference using lead versus

leather as far as producing better spark.

Note: Wide variation in flint use. Replacement may be needed in as few as 20 shots or as many as 150 shots. Common to see 60 to 100 shots per flint, with knapping as required after every battle's 10-16 shots.

Charleville 1766 Musket Sling

One-piece sling in photo above employs full-frame buckle. Can be made tight and

adjusted for length, but with some difficulty.

One-piece sling in photo above employs

full-frame buckle with

prong/tongue removed to allow tight sling with slightly quicker lengthening and shortening.

One-piece sling in photo above employs full-frame buckle with

prong/tongue (strung in the manner of a D/half-frame buckle), allowing

near-tightness and quick adjustment.

When removing barrel for cleaning, fully loosened sling will allow swiveled band

to slip over end of barrel, saving disassembly of sling by trigger guard.

Two-piece sling with long ties outside for easy viewing/adjusting. Thanks to

Brian Herkalo!

Click here for supplier

Cleaning

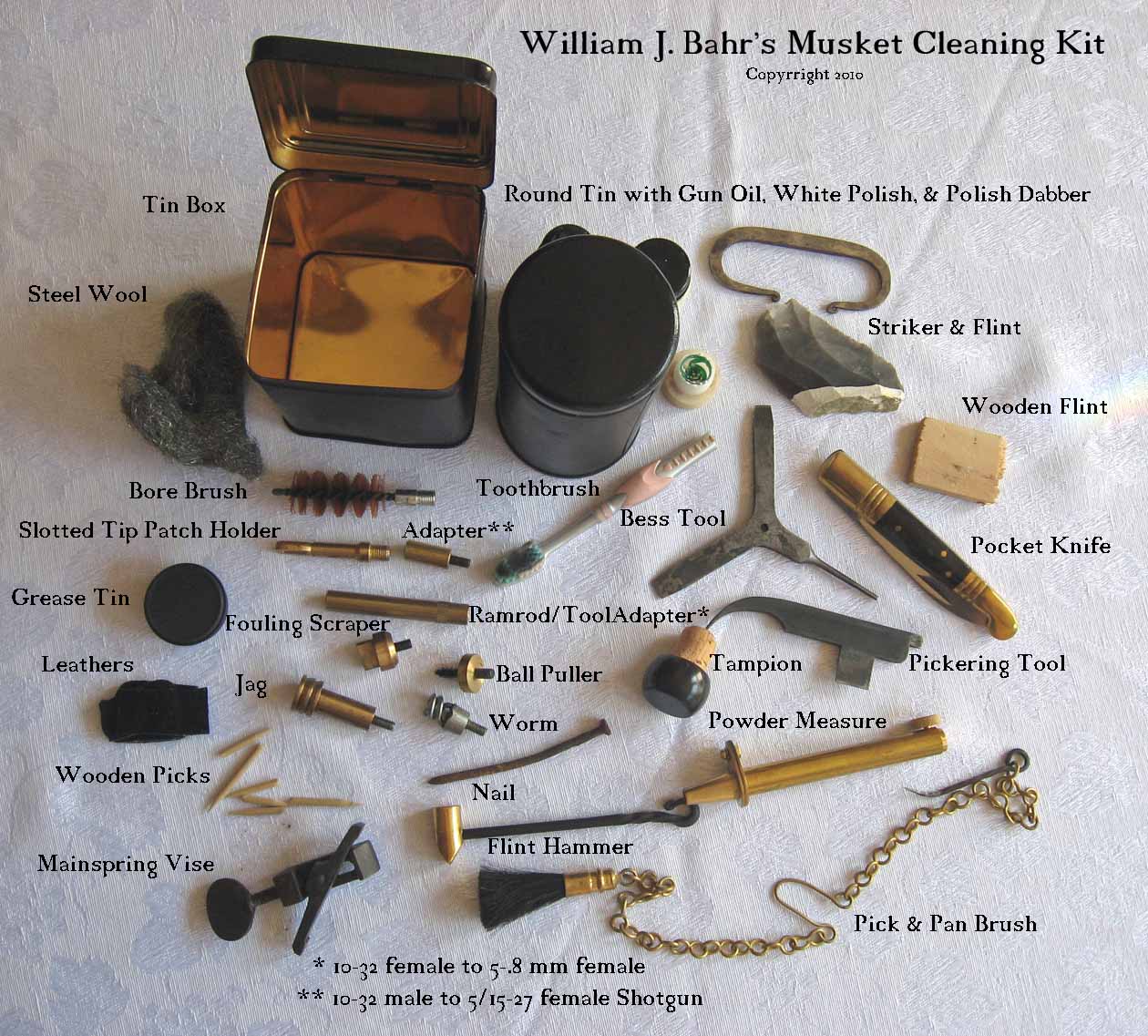

Musket Cleaning Kit

Charleville 1766 Lock

Failure to keep your musket clean, dry, and

lubricated will quickly lead to pitting from corrosive gun powder, rusting from

the weather, and extra wear due to added friction. After each battle in an

event (series or weekend of battles), use a pick & pan brush and clean towel to

remove powder residue from lock, stock, and barrel. At the end of the day,

if a bucket of water is available, you may want to disassemble your musket into

basic parts by removing the appropriate screws and bands. Immerse the lock

and clean it with a toothbrush and cotton swab, as you move the hammer through

its positions. Dry thoroughly and lightly oil. Put the touch hole end of

the barrel into the bucket and pour water down the barrel, doing your best to

clean it along the lines of the thorough barrel cleaning procedure outlined

below, or minimally by pumping water through the barrel by using the ramrod with

cleaning patches and then drying. If you don't have a bucket but do have a

canteen full of water, consider the following field cleaning method: 1.

Disassemble the musket into lock, stock, and barrel. 2. Put a plug

into the vent hole of the barrel and then pour water down the barrel, filling

the barrel and leaning it against something so that it remains upright. If

you don't separate the barrel from the stock (as might be the case with a more

difficult to disassemble Brown Bess or rifle), ensure that the vent hole is not

leaking; otherwise the leaking corrosive liquid will stain your stock. 3.

With a damp rag, clean the lock and then the stock, putting on a light coat of

oil (olive oil is said to have been used during the Revolutionary War). 4.

Clean the barrel as best you can; before drying, turn the barrel upside down to

let as much water as possible to drip out; then dry and clean the barrel by

running the ramrod with clean patches; when patches come out clean, add oil to

the patches to oil the inside of the barrel; then lightly oil the outside of the

barrel. 5. Reassemble the lock, stock, and barrel.

And why not enjoy listening to a Rev War music CD while cleaning your

musket?

At the end of each event, clean your musket as above but using hot, soapy water

to remove the sooty powder residue. Also remove the hammer from the lock

(cock it if needed) and clean and grease behind it. Also, loosen the

flashguard screw and clean behind the flashguard. Be sure to use

properly-sized screwdrivers so as not to strip the unusually small-sized screw

slots. Use Liquid Wrench if screws prove difficult to turn. Be

careful; replacement parts are not inexpensive!

For thorough lock cleaning after each season, first remove lock

from stock (unscrew two lock screws), then disassemble lock (see below).

Best to use a pan to keep parts together; be especially sure to cover drains and

floor vents to prevent losing any part you might drop. After disassembly, immerse

lock parts in hot (preferably soapy) water.

Use toothbrush, toothpick, Q-tip and/or cotton swab to clean crevices. Often

rubbing the steel with an oiled cloth is enough to remove firing stains. Use

fine steel wool or carefully/gently use very fine sandpaper (220 grit) to remove

rust. OTOH, you can use a brass brush, which won't remove the finish, or,

like the Rev War soldiers, use brick dust or emery powder mixed with sweet oil

(olive oil) . But no need to overdo it. Unless you belong to a French unit honor guard

with gleaming muskets, you'll want your musket to age gracefully. Rinse with hot, clean water. Dry (use blow

dryer if desired to avoid rust in tight spaces), then lightly oil, then

reassemble (see below).

Note: for those not able to frequently and thoroughly clean their locks,

consider lubricating the moving lock parts with marine trailer wheel bearing

grease. Such grease is water resistant and allows dunking the lock in

water to quickly remove most powder residue but with minimal rust effects.

Note: Place loose screws on a saucer or in a container to avoid losing

them. If cleaning in or near a sink, place screen over the drain to avoid

lost parts. Also best to use an area where parts can be easily seen and

dropped parts easily found. Use good, properly-fitting screwdrivers so as not to strip

expensive screw heads.

Note: Photos show lock uncocked.

Here is a quick list to disassemble

lock (Pedersoli

reproduction model pictured above):

1. (Before removing from stock,) put the lock into the half-cock position (allows for easier removal of

mainspring & reassembly of hammer).

2. Unscrew the jaw from the hammer.

3. Remove Q (hammer) screw and P (washer, if applicable)

4. Remove K (thick head, medium screw, medium shank) and J

(medium/feather spring; compress first using vise).

5. Remove N (flashguard and feather spring screw - long

screw, long shank (unthreaded portion)) and L (frizzen).

6. Remove I (small screw, no shank) holding H (pan

assembly).

7. Remove G (small screw, medium shank) holding small/sear spring.

8. Compress Mainspring Vise on A (main spring) to release D

(bridle), B (tumbler), and C (sear). You are

advised not to remove the main spring's screw.

9. Remove E2 (medium screw, medium shank-more thread) and E1 (medium

screw, large shank-less thread).

10. Release and remove Mainspring Vise.

Not counting any flint, washer, or flashguard (parts

extra from the manufacturer) and with the hammer disassembled, you should have 18 separate parts in hand.

Clean, dry, and lightly oil (removing excess) lock parts as advised above.

Note: Photos show lock uncocked.

To assemble/reassemble lock (Pedersoli reproduction model):

1. Compress main spring A using Mainspring Vise (and possibly large

pliers to help get started if you have a smaller vise (best to have vise handle

on top, smaller part of spring)) to allow for insertion of

B

(tumbler).

2. Insert B (tumbler) into position pictured.

3. Insert D (bridle), screwing down with E2

(medium screw, medium shank-more thread).

Do not confuse E2

with E1 (less thread) or K, which has a slightly thicker head, is slightly smaller, and

has fewer threads.

4. Insert C (sear), screwing down with E1

(medium screw, large shank). Uncompress main spring A.

5. Insert G (small screw, medium shank) through sear spring

F and screw partially into hole; compress spring with heavy thumb pressure,

inserting spring edge into slot, then tighten G while fully inserting

spring into slot.

6. Insert H (pan assembly) and screw down with I (small

screw, no shank).

7. Insert and compress feather spring J and screw down with K

(thick head, medium screw, medium shank).

8. Compress J (feather spring) with Mainspring Vise and position

frizzen L and flashguard M, screwing down with N

(long screw, long shank). Release vise.

9. Grease (marine grease best, considering event cleaning with water) underside of hammer O , place hammer on square,

pull back

one position to half-cocked so that the hammer can be correctly attached, adding

P (if required), and screwing down with Q (with its underside

greased).

Ensure that screw is tight enough so that hammer does not wiggle sideways in

half-cocked position (a point of troop inspection).

10. Seat lock in stock. If necessary adjust trigger to facilitate

seating. Screw down lock with the two stock screws.

11. Assemble flint jaw and install flint (with leather or lead holder)

with sharp forward edge aligned so that it will squarely meet top 1/3 of closed frizzen.

Note: flint may need to be turned "upside down" ( to meet top 1/3 of closed frizzen.

Ensure that left side of flint will not hit barrel when trigger pulled.

Beware: flint is sharp and can cut flesh easily!

12. If not using soon, store in uncocked position, with frizzen open, and

with flint jaw/cap loosened. If storing with flint loose in jaw, be sure

to tighten the flint jaw before heading to the field to avoid misfiring or

losing the flint altogether.

Alternate/original term translation:

cap =

jaw; cock = hammer; hammer, steel, or battery = frizzen

Disassembly/cleaning/assembly may take about an hour.

For thorough barrel cleaning after each event,

1. Remove the barrel from the stock and put the touch-hole end of the barrel into a bucket of hot, soapy water.

2. Holding the end of the barrel near vertical, pour soapy water down the

barrel a number of times, with the water exiting from the touch-hole.

3. Having put the Ramrod Tool Adapter on the ramrod, attach in turn the

(12 gauge shotgun bore) Brush, Jag, and Fouling Scraper, running each down the barrel

several times, gently twisting the Fouling Scraper in a clockwise. If gets

stuck, do not turn counter-clockwise too many time to risk losing it.

4. Attach the Slotted Tip Patch Holder or the Worm to the ramrod, and run

one or two cleaning patches

(2.5 inch sq or appropriately free-handed) down the barrel, pulling up

soapy water on the up-strokes.

5. Remove the ramrod and pour clean hot water down the barrel until the

water from the touch-hole runs clean.

6. Make additional clean patch runs with the ramrod until the patches show

absolutely no black powder residue.

7. Put a new, lightly-oiled cleaning patch on the ram road and oil the

barrel.

8. Lightly oil the outside of the barrel.

Note: before battle, some prefer to run a clean patch down the barrel to

remove any oil and enhance powder flow down the barrel.

For thorough stock cleaning after each event, use a clean, moist rag,

drying and finishing-up with a light oil. Some prefer linseed oil.

Before putting your musket into storage at the end of the season, remove

and oil/polish the leather sling and then remove and clean/oil the trigger

mechanism. Reassemble.

For rust removal, use a brass brush, steel wool, or a period brick dust compound (or very

carefully use very fine sandpaper/emory-cloth, minimum 220 grit), then oil.

Cleaning after each event may take about half an hour.

Notes:

1. Don't forget to keep all screw threads

lubricated, especially after cleaning with water.

This includes machine screws, threaded tools, ramrods, etc.

2. Tie a cleaning rag to your cartridge box to clean your musket

immediately after firing.

3. When possible, after cleaning intricate parts with water, use a hair

dryer to make sure parts are completely dry to avoid rusting.

See photo below as to why you need to clean your musket (courtesy of NWTA)

And perhaps their flints weren't sharp? Here's a nice video on an easy way to sharpen/knap flint (in a vise). Click on link below:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JQx_xBhpQt0&ab_channel=capandball

Using knapping hammer to knap on the run

Also make sure your flint is properly seated in the flint jaw. Make sure to give the flint the greatest stroke over the frizzen, perhaps turning the flint "upside down" in the jaw to maximize sparks.

Caveat lector: reader beware!

While the author is happy to share this best-to-his-knowledge information and

appreciates your reading it, he can assume no responsibility for how you put it

to use.

The appearance of links to/from other sites does not imply endorsement.

Feedback and corrections are always welcome!

Note: Here are photos of locks from a Brown Bess musket (courtesy of Track of the Wolf) and a Charleville 1763 pistol. Here's a link to Brown Bess cleaning.

Here is a quick list to disassemble (Charlesville pistol

reproduction model pictured above):

1. Put the lock into the half-cock position (allows for easier removal of

mainspring & reassembly of hammer).

2. Unscrew the jaw from the hammer.

3. Remove Q (hammer) screw and P (washer, if applicable)

4. Compress J

(medium/feather spring) using vice.

5. Remove N (flashguard and feather spring screw - long

screw, long shank (unthreaded portion)) and L (frizzen).

6. Compress Mainspring Vise on A (main spring) and remove A to release D

(bridle), B (tumbler), and C (sear).

7. Remove screw which was hidden by the mainspring to remove J

(feather spring).

7. Remove I (small screw, no shank) holding H (pan

assembly).

8. Remove G (small screw, medium shank) holding small/sear spring.

9. Remove E2 (medium screw, medium shank) and E1 (medium

screw, large shank).

Clean, dry, and oil lock parts as advised above.

To assemble/reassemble (Charlesville pistol reproduction model

pictured above):

1. Insert screw to attach J (feather spring).

2. Insert B (tumbler) into position pictured.

3. Insert D (bridle), screwing down with E2

(medium screw, medium shank).

4. Insert C (sear), screwing down with E1

(medium screw, medium shank).

5. Insert G (small screw, medium shank) through sear spring

F and screw partially into hole; compress spring with heavy thumb pressure

or pliers,

inserting spring edge into slot, then tighten G while fully inserting

spring into slot.

6. Insert and uncompress main spring A.

7. Insert H (pan assembly) and screw down with I (small

screw, no shank).

8. Compress J (feather spring) with Mainspring Vise and position

frizzen L and flashguard M, screwing down with N

(long screw, long shank).

9. Grease underside of hammer O , place hammer on square, pull back

one position to half-cocked so that the hammer can be correctly attached, adding

P (if required), and screwing down with Q (with its underside

greased).

Ensure that screw is tight enough so that hammer does not wiggle sideways in

half-cocked position (a point of troop inspection).

10. Assemble flint jaw and install flint (with leather or lead holder)

with sharp forward edge aligned so that it will squarely meet top 1/3 of closed

frizzen.

Note: flint may need to be turned upside down to meet top 1/3 of closed

frizzen.

Ensure that left side of flint will not hit barrel when trigger pulled.

Beware: flint is sharp and can cut flesh easily!

11. If not using soon, store in uncocked position, with frizzen open, and

with flint jaw/cap loosened. If storing with flint loose in jaw, be sure

to tighten the flint jaw before heading to the field to avoid misfiring or

losing the flint altogether.

Alternate/original term translation:

cap =

jaw; cock = hammer; hammer, steel, or battery = frizzen

Click for action

Season 3, Episode 5: "Hypocrisy,

Fraud, and Tyranny"

Click for youtube action

Copyright 2011-2025 W Bahr

Musket Slings, Flints, and Accessories (Vendor)

Pedersoli 1766 Charleville Musket Parts

Dangerous Muzzleloading Practices

Gunflint Sharpening Gunflint Sharpening Gunflint Sharpening

Gunflint Making 1 Gunflint Making 2

"If you have a hard frizzen and matched main and feather springs, a flint will last 100 strikes." Al Potyen, experienced reenactor, 2VA Regt, NWTA

National Park Service's 18th Century Musket Manual -- Belatedly discovered on 11/17/13 ; numerous topics; very interesting!!

Flintlock Safety and Other Tips

Flintlock FAQs

Field Cleaning

of Musket Video

Flintlock Field Cleaning

Video

Five Guns

You Need Too Know From The American Revolution

Flintlock Parts More Flintlock Parts

Pedersoli Pedersoli Instructions

Cleaning and Care for

Flintlocks

From Bright Steel to

Brown: The Colour of British Musket Barrels, 1755-1865

Vendors:

Dixie Gun Works,

Jarnagin,

Jas. Townsend and Son,

Loyalist Arms ,

Track of the Wolf

Note: It has been said that, even when

made-in-India Charleville muskets are of good quality and relatively inexpensive,

standard replacement parts are not available. Please let us know if

otherwise.

"Hanger [British Colonel] is emphatic that never in his life did he see better rifles than those made in America or men who shot better. “They are made,” he says, “in Lancaster and two or three neighbouring towns in that vicinity in Pennsylvania. The barrels weigh about six pounds two or three ounces, carry a ball no larger than thirty-six to the pound, and are three feet three inches long. I have often asked what was the most they thought they could do with their rifle. They have replied that they thought they were generally sure of splitting a man’s head at 200 yards, for so they termed their hitting the head. I have also asked several whether they could hit a man at 400 yards. They have replied certainly, or shoot very near him,”[3] as indeed is evinced by Hanger’s anecdote. Supposed requirement for joining Daniel Morgan's (Virginia) Riflemen was to be able to hit an orange at 300 yards. Another reported requirement was being able to hit a 7" square at 250 yards. Supposedly, renowned rifleman Timothy Murphy, upon prompting by Benedict Arnold and Daniel Morgan, fired four shots at British Brigadier General Simon Fraser, who was leading a critical reconnaissance in force over 300 yards away. Murphy is said to have brought him down on the third shot. Murphy is also said to have brought down Sir Francis Clerke, aide-de-camp to General Burgoyne, as he rode upon the field to deliver orders from Burgoyne to fall back, orders that never reached the intended commanders, all leading to the British surrender at Saratoga.

Note: As astounding as it was then, according to Wikipedia, modern snipers with specialized gear have killed at up to and slightly over 2 miles in range (2 times the 1760 yards in a mile), about 9 times the 400 yard distance of Rev War marksmen! https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Longest_recorded_sniper_kills

"Hanger contrasts the American rifle with the British Brown Bess: “I do maintain that no man was ever killed at 200 yards by a common soldier’s musket by the person who aimed at him. A soldier’s musket, if not exceeding badly bored and very crooked as many are, will strike the figure of a man at 80 yards; it may even at 100 yards; but a soldier must be very unfortunate indeed who shall be wounded by a common musket at 150 yards, provided his antagonist aims at him; and as to firing at a man at 200 yards with a common musket, you may just as well fire at the moon and have the same hopes of hitting your object.”[4]"

Note: To achieve this accuracy, musket barrels were rifled. Barrel lengths for Rev War rifles varied from 32 to over 48 inches. Calibers were .25 to .62, with .40 to .48 cal most common. The rifling twist depended on the bore, with the larger the bore the slower the twist. One turn/twist in 48 inches would be good for around .40 cal. A .62 cal Jaeger would be one in 70 inches. So, figuring a 48 inch barrel, a .40 caliber might have 1 complete turn, and a .62 caliber would have 69% of a turn. More info on rifles. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Long_rifle

Note: As regards the concepts of aiming a "firelock," as observed by Don Hollway in a discourse on matchlocks: "In fact to take aim and shoot a specific person on purpose, even on the battlefield, was considered murder, but if you aimed at a whole bunch of them and happened to hit one of them, that was an act of God." Ref: https://www.quora.com/What-type-of-musket-was-used-during-the-time-period-of-Alexandre-Dumas-The-Three-Musketeers/answer/Don-Hollway Referenced video of matchlock firing (1-2 shots/minute): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2KTS8PQ06Qo&feature=emb_err_woyt

The Amazing Ferguson Breech-loading Rifle

Note: The six-foot English longbow was made of hew wood and had a draw weight of between 80 and 150 pounds. Its effective range was between 200 and 400 yards, nominally 350 yards. It is said that some could send arrows up to 650 yards (500 meters).

Note: According to a Civil War reenactor: A smoothbore musket has an effective range of 75-100 yards. He also said that it took 16 pounds of lead to kill a man. As mentioned above, a Charleville ball weighed around .84 ounces, yielding 19 shots in 16 pounds. 16 pounds to kill a man? Hard to believe, well unless he was several 200+ hundred yards out!!! The same reenactor said a 0.58 caliber Minieball (rifled) has an effective range of 300-900 yards when using 61-65 grains of 2 or 3F powder, when yielding 3 aimed shots per minute.

Note: Here is some recently acquired

musket range/accuracy information from Alex Burns that I have not yet processed:

https://kabinettskriege.blogspot.com/2018/01/how-close-ranged-were-mid-eighteenth.html

and, of possible interest:

https://kabinettskriege.blogspot.com/2021/03/grenades-in-mid-eighteenth-century.html

More information

Gunpowder

constituents: 15% charcoal, 10% sulfur, and 75% saltpeter. Sulfur (yellow/gold)

burns at a relatively low temperature (sort of like kindling), carbon (black) is

the main fuel, and saltpeter (gray) is the oxidizer, the intense source of

oxygen, the ignition accelerant. Not an accident is that black, gray, and gold

are the school colors of the United States Military Academy at West Point.

See more farther below.

Tactics are outgrowths

of technology. With the advent of gunpowder and the use of the musket as a

weapon, battlefields were now smoky and noisy. Leaders needed to maintain

control, via drums, bugles, and keeping their men close. Musket firing in

volleys maintained the speed of loading and firing. The psychological effect of

a round of mass fire, where many inaccurate muskets managed to hit at least

something in an effort to shock and awe, was followed either immediately or

after several more rounds by a massed bayonet charge. The speed of firing and

cohesive unit movement was a critical focus of Prussian army drill. [Military

tactics later changed with the advent of the rifled musket and Minie ball for

speed and accuracy, allowing for dispersion of units, with soldiers now more

often able to move independently as seen in America’s Civil War.] Note: P 54:

The author writes, “Under the best possible conditions, a well-trained and

well-supplied soldier could load and shoot four or five times per minute.” While

it is said that a well-trained Prussian soldier (someone who spent many years

practicing) could get off rounds up to six times a minute, some of the very best

modern-day Rev War reenactors can barely make four times per minute. Many times

in battle involving unit movement, a soldier would be lucky to get off one round

per minute.

"GUN OF THE DAY-French Model 1768 Flintlock Musket"

"The U.S. Pattern 1795 musket [Springfield] was based on this French model. This New

Hampshire-marked musket was imported in October, 1776 and saw service with

Edward Cox, a journeyman farmer who enlisted with his brother, John, in the 2nd

Regiment [VA], Continental Army.

John Parker's "musket" has been identified as a fowling piece, not a Charleville as per Lexington statue above.

BTW, the

French Charleville .69

caliber muskets were first presented to George Washington by Lafayette. One

estimate of Lafayette's deliveries is 25,000 Charlevilles. The US later

commissioned the 1795 Springfield musket based upon the Charleville design. The

Springfields are the crossed muskets which have become the US Infantry

insignia.

* Gunpower historical note from Wikipedia: "At least since antiquity, grains of wheat or barley were used by Mediterranean traders to define units of mass; along with other seeds, especially those of the carob tree. According to a longstanding tradition, 1 carat (the mass of a carob seed) was equivalent to the weight of 4 wheat grains or 3 barleycorns.[7]:95 Since the weights of these seeds are highly variable, especially that of the cereals as a function of moisture, this is a convention more than an absolute law.[29]:120–1" An avoirdupois/international pound is defined as 7000 grains [previously 1 London/English pound = 7200 grains powder]. Gunpowder grades: F for Fine, the more F's, the finer (eg. Fg = coarse grain; FFg = medium grain; FFFg = fine grain; the "g" designation stands for sporting (shooter's) grade). Also gunpowder mixed with water could substitute in hard times for ink. Mixed with rum, it did the job for making tatoos. Gunpowder, the earliest known explosive and invented in the 800's in China, is comprised of charcoal (black), sulfur (gold), and potassium nitrate (gray). Black, gold, and gray are the colors for the United States Military Academy at West Point.

Other notes: The flintlock was likely invented by Marin le Bourgeoys (1550-1634). Flintlocks were first used by fusiliers (fusil = French for gun, primarily a flintlock), who with this new safer-around-powder-than-matchlocks, were assigned to guard dangerous, powder-laden artillery and baggage trains; fusiliers were often awarded distinctive hats to wear. Muskets were mostly military issue. A fowler smoothbore (fowling piece) was essentially a shotgun used by civilians primarily for waterfowl (birds). In many cases, Brown Besses left over from the French and Indian War were sawed off to make shotguns for hunting. Various size pellets were made for various game, to ensure the maximum probability of downing the game by adjusting size and number of shot. Rifles were usually .25 to .6 caliber (.42 to .48 most common) with the stock covering most, if not all, of the barrel (not allowing an easy attachment for a bayonet, which even if it worked may have obstructed the sight, negating the main advantage of the rifle). Rifle bore was also too small for a plug bayonet; need at least 50 caliber to hold a decent bayonet. Some rifles even had octagonal barrels (commonly made bar iron blanks in octagonal form didn't need to be further forged/turned/rounded and were easier to drill and groove, due to easier centering and gripping), making retrofit to hold a bayonet even harder. Thus, riflemen who were reloading were prime targets for bayonet charges. Riflemen took advantage of the long range of the rifle both in war and peace. Herds of prey at a distance could not detect the rifle report and would likely not scatter after the first of them went down. Immigrant German craftsmen, familiar with the Jaeger (hunter) rifles used in Germany, produced the longer, smaller-caliber Pennsylvania and Kentucky long rifles, ideal for American frontier use. For rifle barrel making, check out this website: http://www.flintriflesmith.com/ToolsandTechniques/barrel_making.htm

More notes: Rule-of-thumb Ranges: Musket: 50-100 yards Rifle 200 yards. Rifles 2-4x more range than musket. Quite often many more bayonet wounds than ball wounds.

Note: Before the

Socket Bayonet was Plug Bayonet (bayonet handle fit into the barrel of fowling piece):

Revolutionary War Muskets & Rifles

1760 yards in a mile. 176 yards in a tenth of a mile. 440 yards in a quarter

mile.

The US Department of Defense: Effective range is “The maximum distance at which

a weapon may be expected to be accurate and achieve the desired result.” What

this means in any specific situation is arguable.

Smoothbore musket: Maximum effective range: 100 to 200 yards. Average effective

range: 50 to 75 yards.

Don't fire until you see the whites of their eyes (30 yards? See link

below.).

The smoothbore musket generally allowed no more than 300 yards with any

accuracy. Fortification designers planned on "musket shot" range of 300 yards

regardless of inaccuracy.

The maximum range of the bullet was 1,200 yards.

Rule of thumb for smoothbore effective range: 50-100 yards.

Massed firing control: In the time it took an opponent to reload (1-4

shots/minute) well-trained soldiers could outrun the range of a musket.

Therefore, Important for commanders to develop effective firing and

bayonet-rushing strategies.

Supposed requirement for joining Daniel Morgan's (Virginia, American

Revolutionary War) Riflemen was to be able to hit an orange at 300 yards. One

reported requirement was being able to hit a 7" square at 250 yards. A few

marksmen were able to hit targets at 400 yards.

Longbow effective range 200-400 yards, nominally 350 yards, while some could

send arrows up to 650 yards.

TAKE NOTICE: According to the

Journal of

the American Revolution, the background "Take Notice" poster was not of

Revolutionary War origin

but came from the mobilization for the "Quasi-War" with France in 1798.

Click here to view a set of "Take

Notice" Manual of Arms products.

Suggestions, click here to send email.

Original work © 2017-2025, W. Bahr

Return to Reenactment Cover Page

Grand Union

If you like this type of information, you'll love:

View Revolutionary War Reenactment YouTube Playlist (30+ YouTubes) click:

Also:

From Quora: How long did it take for a soldier during the American Revolution to reload a rifle?

"For rifles, probably 1 shot/minute or a 60 second reload time until barrel fouling occurred. 0 to 6 shots/minute for muskets. 6, supposedly by well-trained Prussians. 0 shots/minute for a scared militiaman. This results in an undefined (division by 0) answer for the militaman and a 10 second reload time (almost unbelievable) by a well-trained Prussian (possibly for Hessians as well, but then again, they spent their lives practicing). Modern-day videos show a British reenactor barely making 4 shots per minute or a 15 second reload time. Various tricks can move the shots up to 5 shots/minute (12 seconds). One trick is to start the clock with the first shot, not with its load. Another trick is with ramrods: not reseating them but stabbing them nearby into the ground. Of course, the best times above are likely not met in actual, “fog of war” battlefield conditions with the weapon on the move. More information at Charleville Musket Firing and Cleaning "

Revolutionary War Weapons Don't fire until you see the whites of their eyes (30 yards?)

Inaccuracy of Muskets Round Ball to Jaw Lead Flintlock Flint Holder How Washington Got His Gun Powder Production of Gunpowder During the American Revolution or Production of Gunpowder During the American Revolution

Musket ball 5th Street Laboratory (Philadelphia Armory) Philadelphia Armory Post Rev War Musket Ball Making Von Steuben, Valley Forge, & Drill

Reviews of Revolutionary War Books and More

NB: See my comments to second link above: I might mention the following: 1. Flattening can go quicker with a larger hammer. 2. I stop pounding on my .68 - .64 caliber (for Charleville) round ball when the smashed lead is about 2 inches in diameter. 3. After cutting out the outlined holder and folding it, as you've done, I also add a small triangular notch in the middle of the back of the fold, so that the holder can easily center on the jaw screw. 4. Once I'm satisfied with the results (proof is in the pudding), I make several holders at one time, in order to have ready spares that I keep in my cartridge box along with a couple extra flints.

NB: Comparison: .75 inch = 19.1 millimeter .69 inch caliber = 17.5 millimeter .45 inch caliber = 11.4 millimeter .35 inch caliber = 9 millimeter

Also:

08/31/25: Continued from above: 4YI, about the United States Military Academy at West Point's school colors: Black (carbon), Gray (saltpeter, potassium nitrate), Gold (sulfur)

The chemical reaction of gunpowder

10KNO3 + 3S + 8C → 2K2CO3 +3K2SO4 + 6CO2 + 5N2

REF: https://www.chemistryislife.com/the-chemistry-of-gunpowder

From ChatGPT5:

WJB: What makes gunpowder explosive?

ChatGPT said:

Gunpowder (also called black powder) is explosive because of the way its ingredients chemically react when ignited.

It’s a mixture, not a compound, of three main parts:

Saltpeter (potassium nitrate, KNO₃) – supplies oxygen.

Charcoal (mostly carbon) – fuel.

Sulfur – lowers ignition temperature and increases the speed of combustion.

Here’s why it explodes:

So, the explosiveness comes from:

![]()

![]() Strategic Advantage:

Strategic Advantage:

![]()

How to Win in War,

Business, and Life

![]()

![]()

![]() Strategy Pure and Simple:

Strategy Pure and Simple:

![]()

Essential Moves for Winning in

Competition and Cooperation

![]()

![]()